Saturday, October 27, 2018 - 7 p.m.

House of Prayer Lutheran Church

7625 Chicago Ave

Richfield, MN 55423

Bryant: Ecstatic Fanfare

Perrine: Temperance

Turnbull: "Everything starts from a dot"

Gotovac: Simfonijsko Kolo

Maslanka: Symphony No. 10 "The River of Time"

GSW presents a program of musical portraits of old and new, and both distant and familiar. The concert will open with American Steven Bryant's bold Ecstatic Fanfare, drawn from his 2010 National Band Association William D. Revelli Award-winning piece, Ecstatic Waters.

We then take a short tour of the art museum with British composer Kit Turnbull's musical interpretation of three paintings by Wassily Kandinsky in "Everything starts from a dot." The concert returns to Minnesota with native son Aaron Perrine's atmospheric impression of the state's own Temperance River in Temperance. An international and ethnic flavor is added by Jackov Gotovac's symphonic portrayal of his native Croatia's circle dance, the kolo.

The concert concludes with the final work of and memorial to the late David Maslanka, his Symphony No. 10 "The River of Time," as completed by his son, Matthew Maslanka.

Unless otherwise noted, our concerts are free and open to the public. Help support our mission to bring great music to the Twin Cities – share this information with your friends. Sign up for our mailing list and receive reminders for our events.

Program Notes

Steven Bryant, Ecstatic Fanfare (2012)

Steven Bryant (b. 1972) is an American composer primarily for wind band. His list of works includes 48 unique compositions, with alternate instrumentation versions yielding a full catalog of 75 items. The “really short” version of his biography, as posted on his website, reads: “Steven Bryant trained for one summer in the mid-1980s as a break-dancer (i.e. forced into lessons by his mother), was the 1987 1/10 scale radio-controlled car racing Arkansas state champion, has a Bacon Number of 1, and has played saxophone with Branford Marsalis on Sleigh Ride. Steven studied composition with John Corigliano at The Juilliard School, Cindy McTee at the University of North Texas, and Francis McBeth at Ouachita University, He resides in Durham, NC with his wife, conductor Verena Moesenbichler-Bryant.” (https://www.stevenbryant.com/, accessed 2018-09-06.)

Ecstatic Fanfare is based on material from Bryant’s 2008 composition Ecstatic Waters for wind ensemble and electronics. The composer writes, “One day in May, 2012, I mentioned to my wife that it might be fun to take the soaring, heroic tutti music from that earlier work and turn it into a short fanfare ‘someday.’ She goaded me into doing it immediately, and so in a panicked three-day composing frenzy, I created this new work, which was premiered by Johann Mösenbichler with the Polizeiorchester Bayern just three short weeks later, followed immediately by my wife conducting it with the World Youth Wind Orchestra Project at the Mid Europe festival in July, 2012.Unlike its source music, this fanfare does not require any electronic elements!”

Bryant described the original music of Ecstatic Waters as “as a pure expression of exuberant joy….The movement grows in momentum, becoming perhaps too exuberant – the initial simplicity evolves into a full-throated brashness bordering on dangerous arrogance and naiveté, though it retreats from the brink and ends by returning to the opening innocence.” Ecstatic Fanfare, however, shows no such retreat, and ends at least as exuberantly as it began.

Aaron Perrine, Temperance (2016)

Aaron Perrine (b. 1979) attended the University of Minnesota at Morris, where he studied trombone and obtained his teaching licensure. He continued his studies at the University of Minnesota where he obtained a M. Ed. in music, and later the University of Iowa for a Ph. D. in composition.

The title of this work refers to the Temperance River, a modest forty-mile waterway originating at Brule Lake (an elongated body of water located about 10 miles south of the US-Canada border) and terminating in Lake Superior, about 80 miles along the shoreline from Duluth or 35 miles from Grand Marais. The mouth of the Temperance River is surrounded by Temperance River State Park.

The composer provides this note concerning the work:

Temperance was commissioned by a consortium of Minnesota universities, colleges and high schools and was premiered by the 2017 Intercollegiate Honor Band at the Minnesota Music Educators Association Midwinter Clinic. From the start, I knew I wanted the piece to be connected to the state of Minnesota: the place I’ve called home for most of my life.

When I think of Minnesota, my mind tends to drift to the scenic stretch of Lake Superior between Duluth and Canada, locally referred to as the North Shore. While there are seemingly countless outdoor destinations along the North Shore from which to choose, the Temperance River has always been a personal favorite. Further, I knew this was an area many of the members of the consortium had likely visited.

After contemplating some of the different directions I might take the work, I became intrigued by the word “temperance.” Most simply, the word is defined as “restraint.” From the chorale-like passages to the moments of nearly static harmony, the idea of “restraint” permeated my thoughts as I composed. Temperance is my response to the beauty, serenity and solitude found along Minnesota’s North Shore.

Kit Turnbull, “Everything starts from a dot” (2016)

British composer Kit Turnbull (b.1969) began his musical career as a keyboard player in a rock band before joining Her Majesty's Royal Marines Band Service in 1991 as a bassoonist. From 1997 he studied composition with Martin Ellerby at the London College of Music where he subsequently became a course leader and composition tutor. He is currently Composition and Arranging tutor to the Royal Air Force Music Services. A recipient of the Silver Medal of the Worshipful Company of Musicians in 1998, he has since completed numerous commissions that have been performed, broadcast and recorded all over the world. (Biography courtesy of https://www.kit-turnbull.com/biography, accessed 2018-09-06.)

“Everything starts from a dot” is a statement attributed to the Russian-born artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), though an exhaustive search by GSW has failed to turn up the specific origin or context of this exact utterance.* Nevertheless, the phrase has been described as “the anthological sentence [i.e., the summation] of Kandinsky” (http://www.artea.com.br/en/?portfolio=kandinsky-everything-stars-from-a-dot, accessed 2018-09-07). Kandinsky was a formative figure in the development of abstract (non-representational) art and a key member of the German Bauhaus school, where he made significant contributions in the theory of art as well through numerous writings, most especially Über des Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art) (1909/1911/1912) and Punkt und Linie zu Fläche (Point and Line to Plane) (1926). Kandinsky was a synesthete, experiencing colors and sounds simultaneously and interchangeably, and his writings frequently compare the properties of music and the visual arts. He perceived in music a truly abstract spirituality, which he sought to impart to painting: “With few exceptions, music has been for some centuries the art which has devoted itself not to the reproduction of natural phenomena, but rather to the expression of the artist’s soul, in musical sound” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 35; translator unknown).

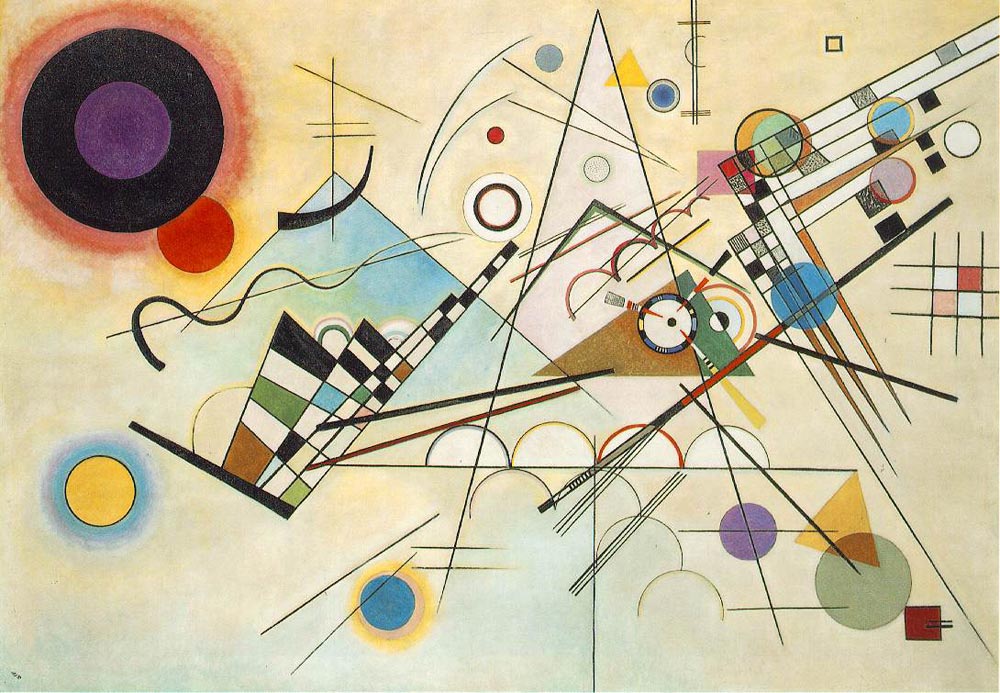

In an exclusive correspondence with Grand Symphonic Winds, composer Kit Turnbull reveals that he has had a long-time interest in Kandinsky. He writes, “I think this started with a poster that I owned (many years ago) of Kandinsky’s Composition VIII. I was always drawn to the individual elements that made up the whole, and I read Concerning the Spiritual in Art for the first time when I started to take an interest in writing music. Kandinsky’s approach to painting seemed to make a lot of sense as an approach to musical composition and I guess I liked his position that music and painting were inextricably linked as art forms. He also spoke of the ‘inner sound of colour’ and I liked that idea, and although I wanted to write something based around Kandinsky’s paintings, it was another 18 years before I approached it.” Turnbull eventually wrote Blue Rider (2011) for solo euphonium and brass band, which is inspired by Composition VIII and two other Kandinsky works, and takes its title from the artistic society/movement Der Blaue Reiter, founded by Kandinsky and several associates in 1911 (and which itself was named after a 1903 painting by Kandinsky).

Composition VIII, 1923

Der Blaue Reiter, 1903

In his second Kandinsky-inspired composition, “Everything starts from a dot” (the quotation marks are part of the title), Turnbull departs somewhat from the spirit of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) and Gunther Schuller’s Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee (1959), and from his own Blue Rider, all of which offer direct musical impressions or representations of the visual subjects that inspired the music. Unlike those works, Turnbull says he was not aiming exactly for the audience to “hear the paintings” in this piece. He says, “with this piece, I think I was rather more trying to create a soundtrack to listen to while looking at the pieces, which is where the additional titles [to the movements] came from. . . .I would look at “Everything starts from a dot” as being my personal reaction to the paintings. If a listener hears this and feels some kind of connection with the artwork then I am happy with that.”

The piece is in three movements. Turnbull makes the following comments about each one:

I. Staccato Dances / On The Points - 1928. Painted in the same year in which Kandinsky completed his text Point and Line to Plane, I saw this painting as a tight grouping of geometric shapes balancing on points, seemingly teetering on the brink of falling, as they vie for the same space on the horizontal surface. [The Bauhaus school had added architecture to its curriculum in 1927, and Kandinsky’s lectures discussed the relationship of art to functional construction. The Guggenheim Museum describes On the Points as the major painting of this period, and which conveys “a teetering balance of diagonals...used to evoke the tension and dynamism inherent in the building up of elements” (Kandinsky: Russian and Bauhaus Years 1915-1933, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1983, p.74).

In a semi-related intersection of music and painting, in 1928 Kandinsky also produced a series of paintings that are themselves after some of the same subjects painted by Victor Hartmann that prompted Mussorgsky's aforementioned piano composition Pictures at an Exhibition.—GSW]

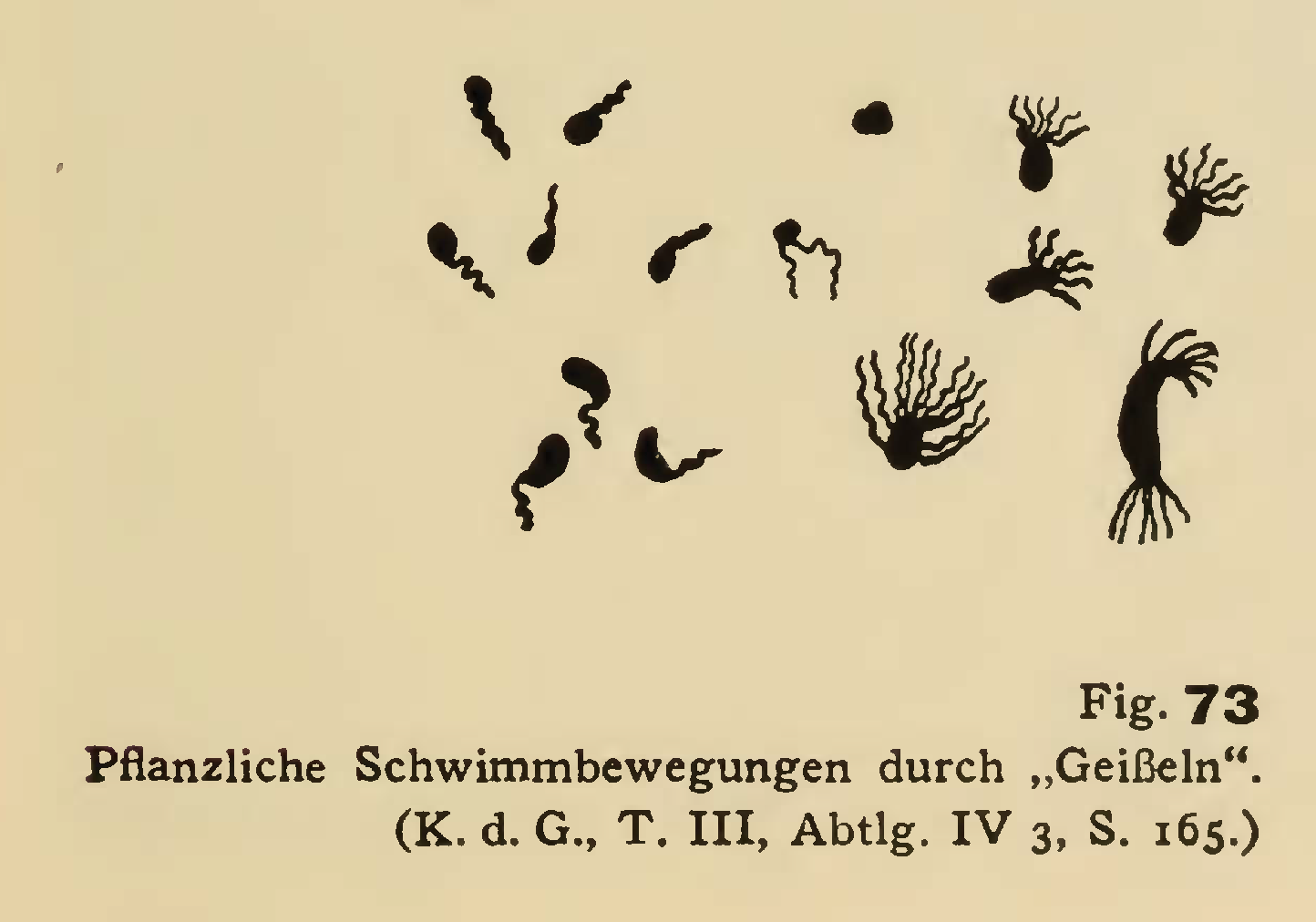

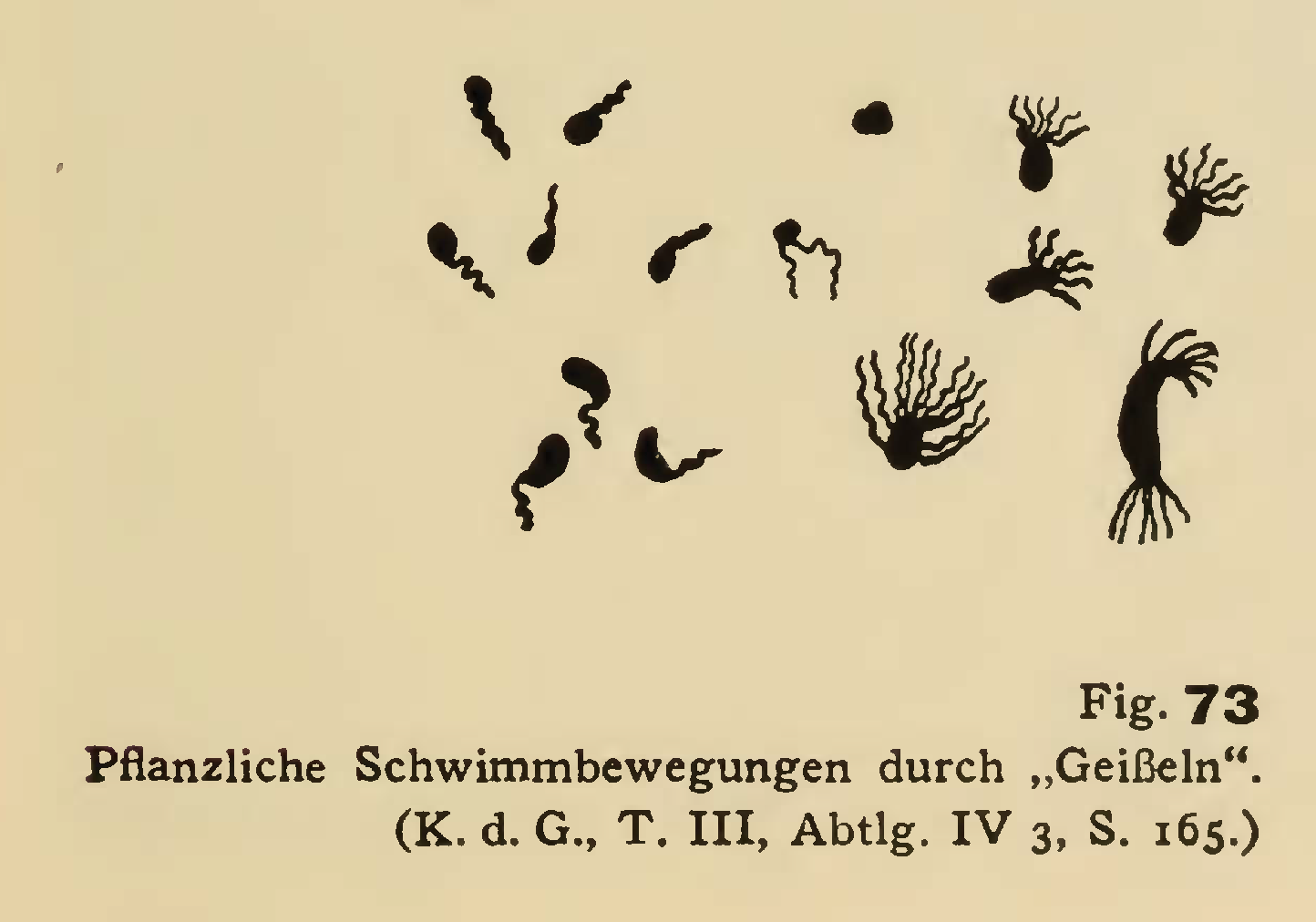

II. Lighter-than-air / Sky Blue - 1940. As his career went on, Kandinsky became more concerned with the depiction of biomorphic shapes. In Sky Blue, these figures (that you might almost call creatures) emerge from the blue background that resembles the sky, floating in seemingly random patterns. [During the years 1934-1944, Kandinsky resided in Paris. He produced a number of paintings that are predominantly blue. Concerning this color, Kandinsky said ,”the deeper you go, the more blue develops the element of calm.” (Wassily Kandinsky & Paola Rapelli, ArtBook Kandinsky, New York: DK Publishing, 1999, p. 120). The authors of Kandinsky in Paris, also published by the Guggenheim museum, observe a connection between the "biomorphic" figures of Sky Blue and Kandinsky's earlier interest in an article on deep-sea life by one G. von Borkow, which included a "greatly enlarged photograph of plankton....Plankton, brine shrimp, snails and larval stages of marine life become small, curving motifs that are evocatively and amusingly rendered in Kandinsky's work (Kandinsky in Paris, 1934-1944, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1985, 69).--GSW]

To his original description, Turnbull adds, “the second movement is in many ways a long, drawn-out musical suspension (my means of creating an atmosphere of floating) and then overlaying that with melodic material that (to me at least) represents the biomorphic shapes.

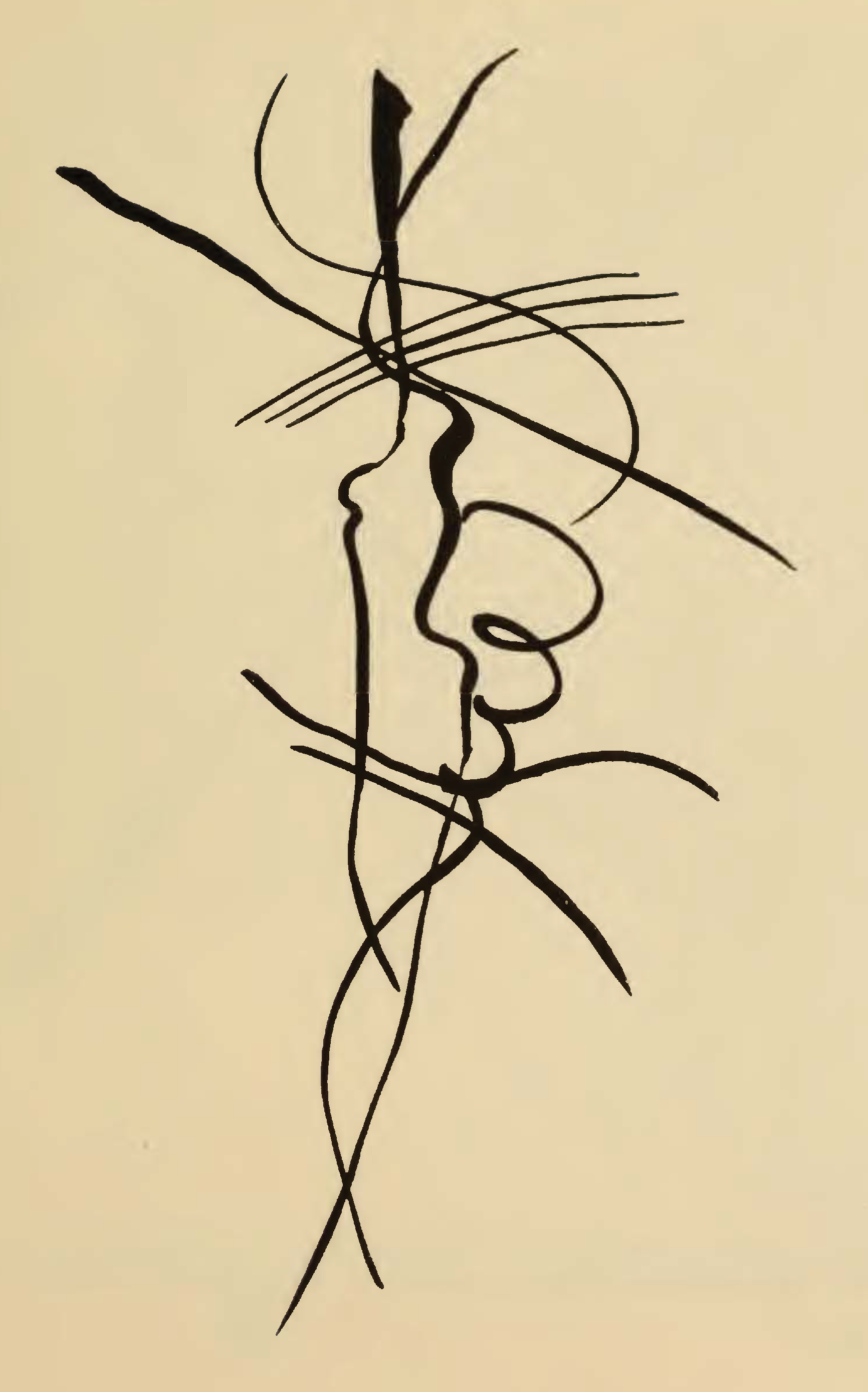

III. Capricious / Violet Wedge - 1919. Painted during his return to Russia, this picture contains a mass of Kandinsky’s trademark lines and squiggles intertwined on a vibrant background, and in the top right corner, the eye is constantly drawn back to the violet wedge.

*GSW was able to find, through examination of Kandinsky’s original 1926 German text Punkt und Linie zu Fläche: Beitrag zur Analyse der malerischen Elemente (Point and Line to Plane: A Contribution to the Analysis of Graphic Elements), the phrase “Also muß hier mit dem Urelement der Malerei angefangen werden—mit dem Punkt,” which may be translated as “so you have to start with the fundamental element of painting—with the point.” The German- language Wikipedia page for Kandinsky (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wassily_Kandinsky) also cites this same text as the source of “Der Punkt ist Urelement, Befruchtung der leeren Fläche,” or “The point is the primary element, the fertilization of the blank area”—though this phrase, too, appears to be a re-translation of something else, as that exact sentence is not found in the 1926 German edition. Nevertheless, it is not far from either of these to a free paraphrase that produces “everything starts from a point (dot),” but it remains a curiosity that this exact English sentence occurs again and again, yet never with any specific citation or context provided.

|

|

|

| On The Points (1928). Oil on canvas. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. | Sky Blue (1940). Oil on canvas. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France. | Violet Wedge - 1919. Oil on canvas. The Tyumen Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Tyumen, Russia. |

| https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-361.php | https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-55.php | https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-630.php |

|

|

|

| Kandinsky cautions against trying to force a recognition of the familiar in a painting, while failing to see and experience the painting itself: “The spectator is also too accustomed to look for the ‘meaning,’ in other words an exterior relationship between the parts of the picture. Our era, materialist in life and therefore in art, has produced a spectator who does not know how to simply put himself in front of a painting, and looks for everything possible in the painting but does not allow the picture to work an effect on him” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art, as translated in Kandinsky & Rapelli, p. 67). | Plants swimming by means of their “tails,” an illustration in Punkt und Linie zu Fläche (1926), p. 99, presumably drawn by Kandinsky, based on an article in Die Kultur der Gegenwart (The Culture of the Present), a German encyclopedia published from 1906 to 1926. |  |

|

||

|

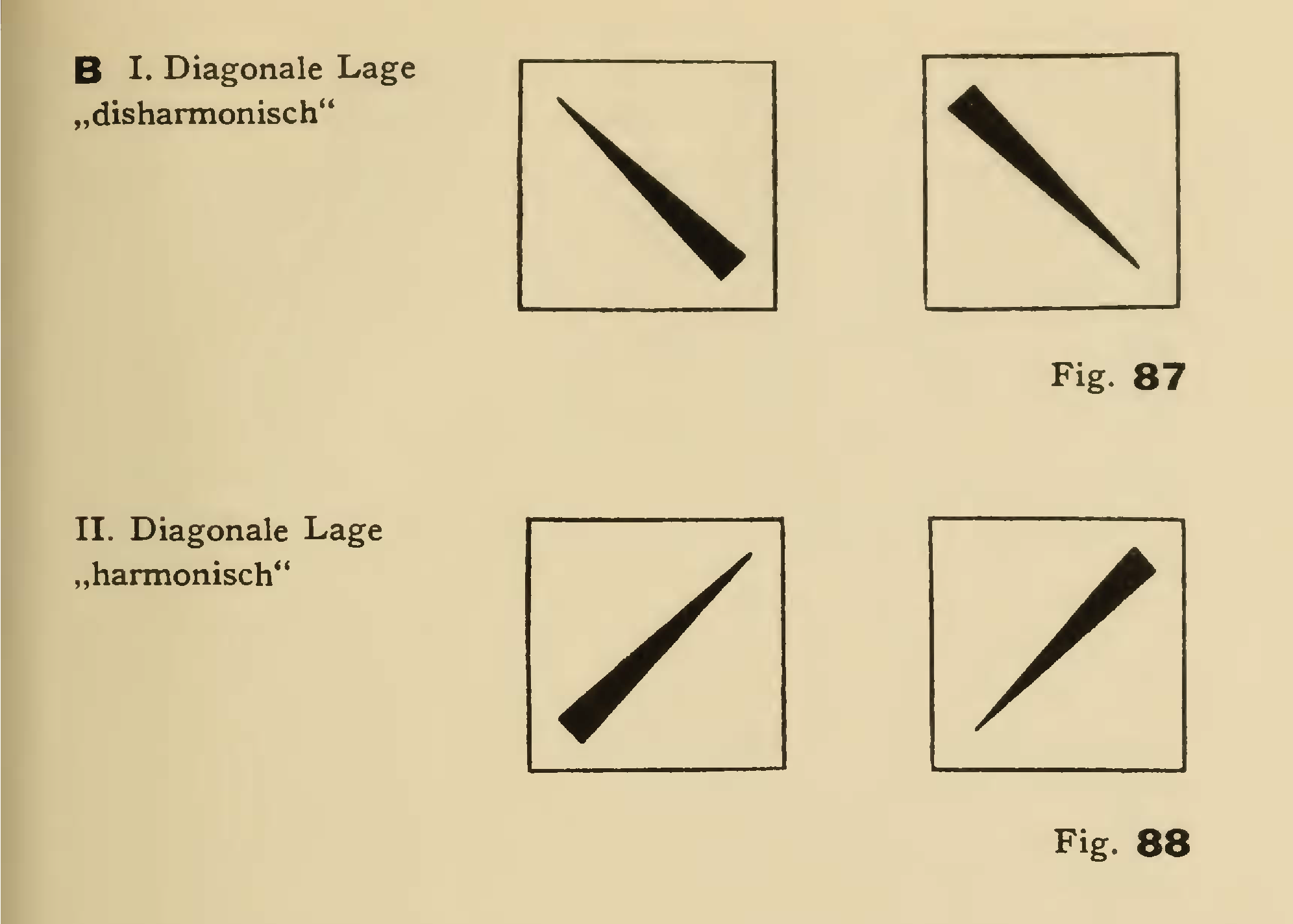

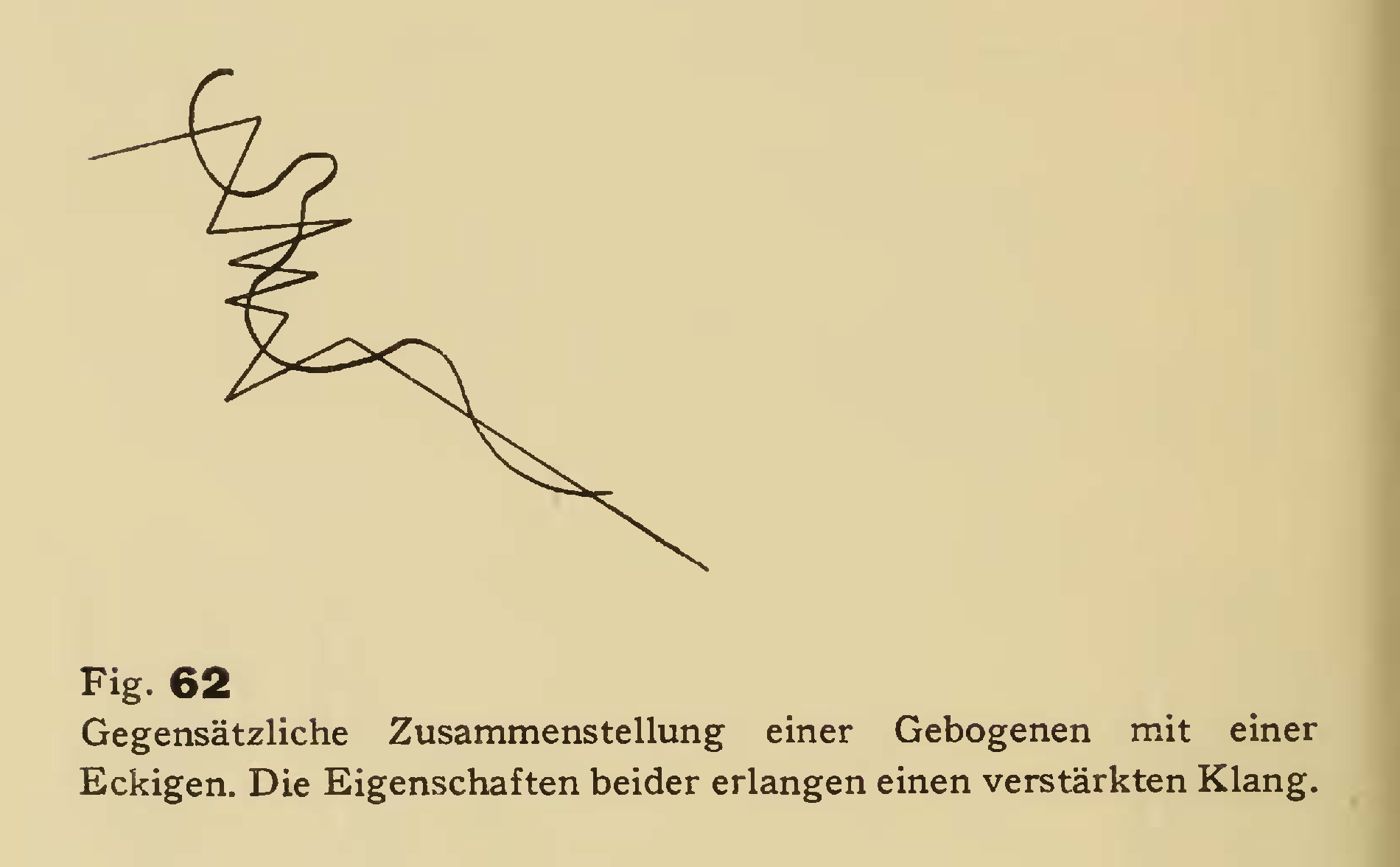

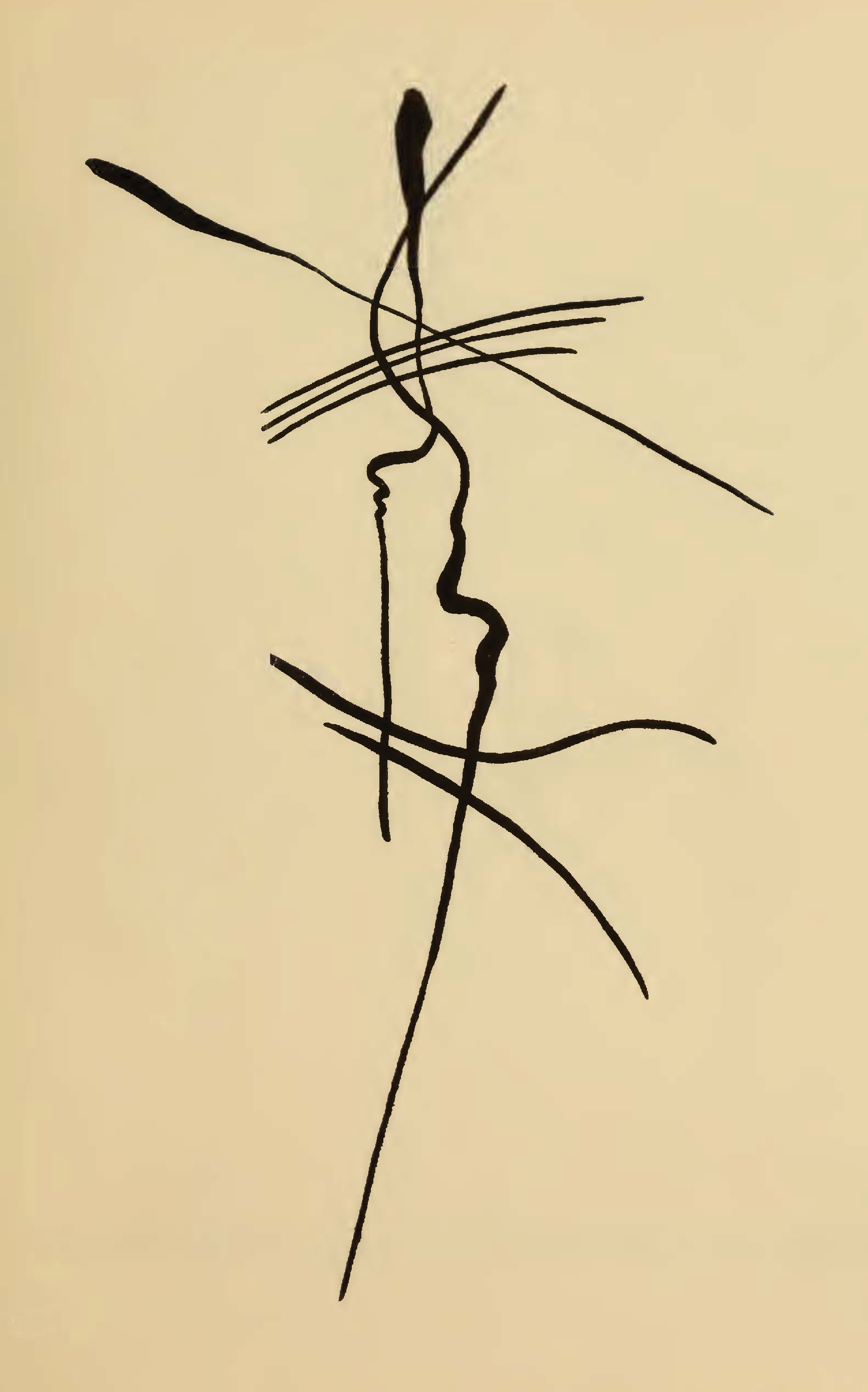

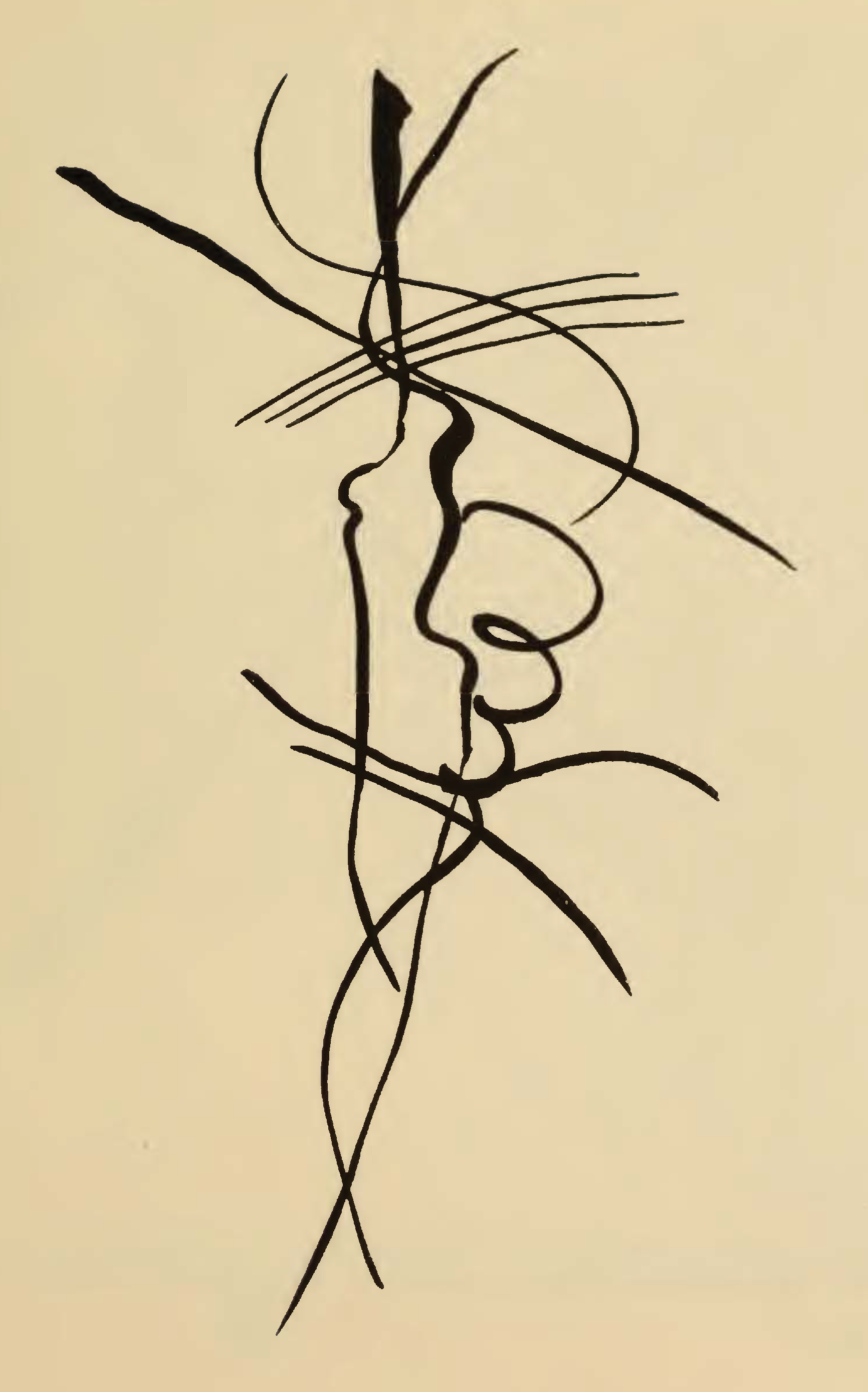

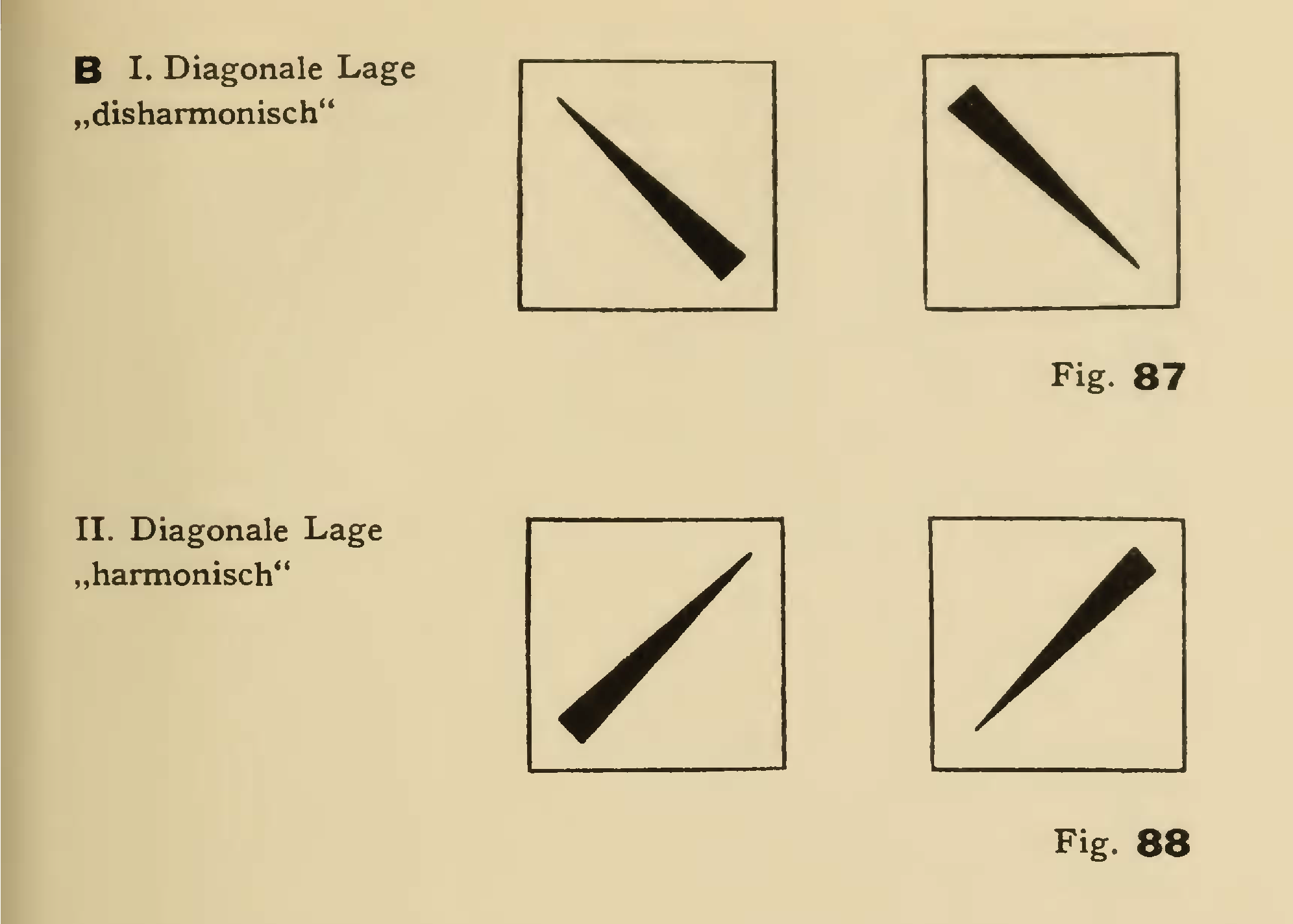

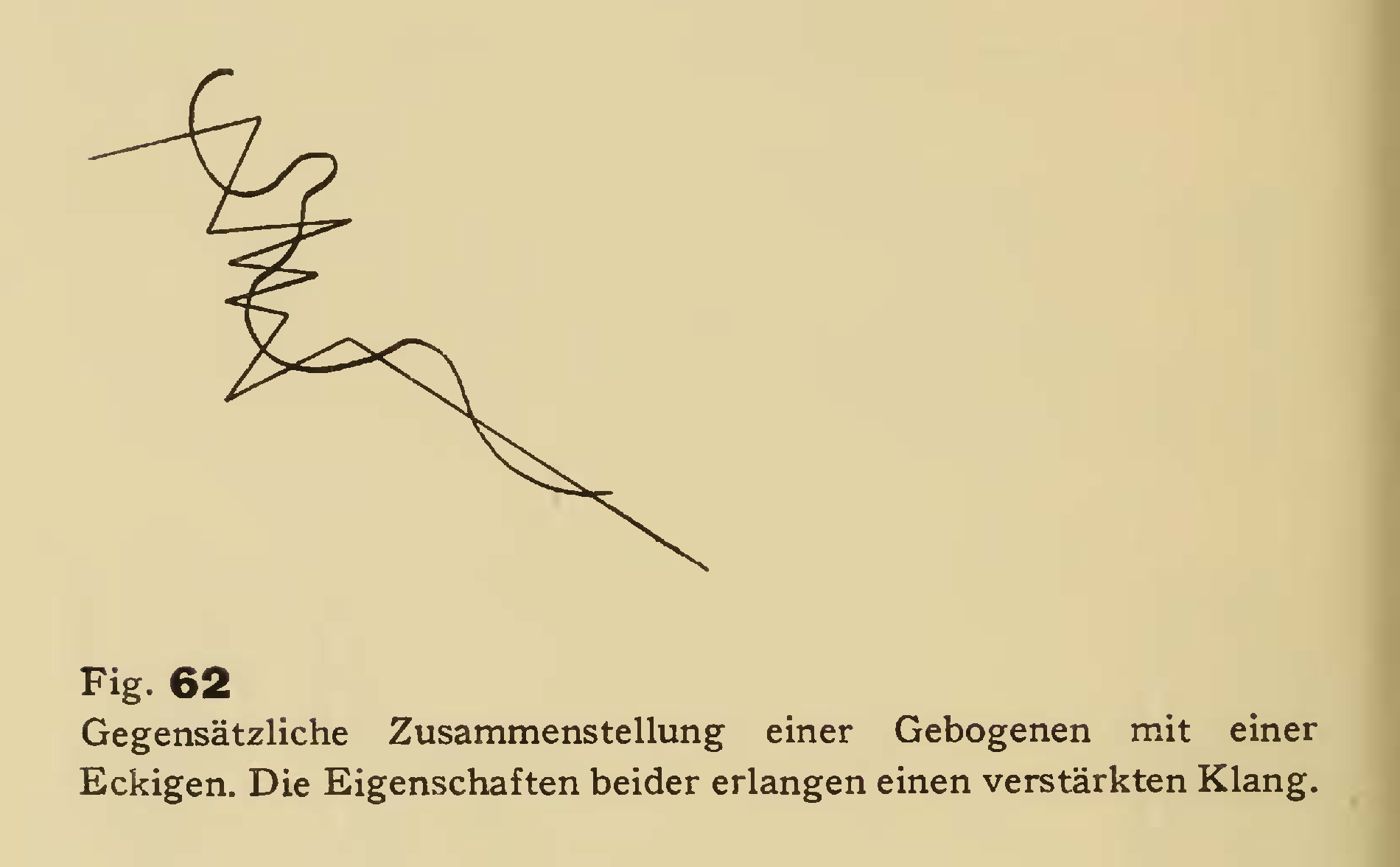

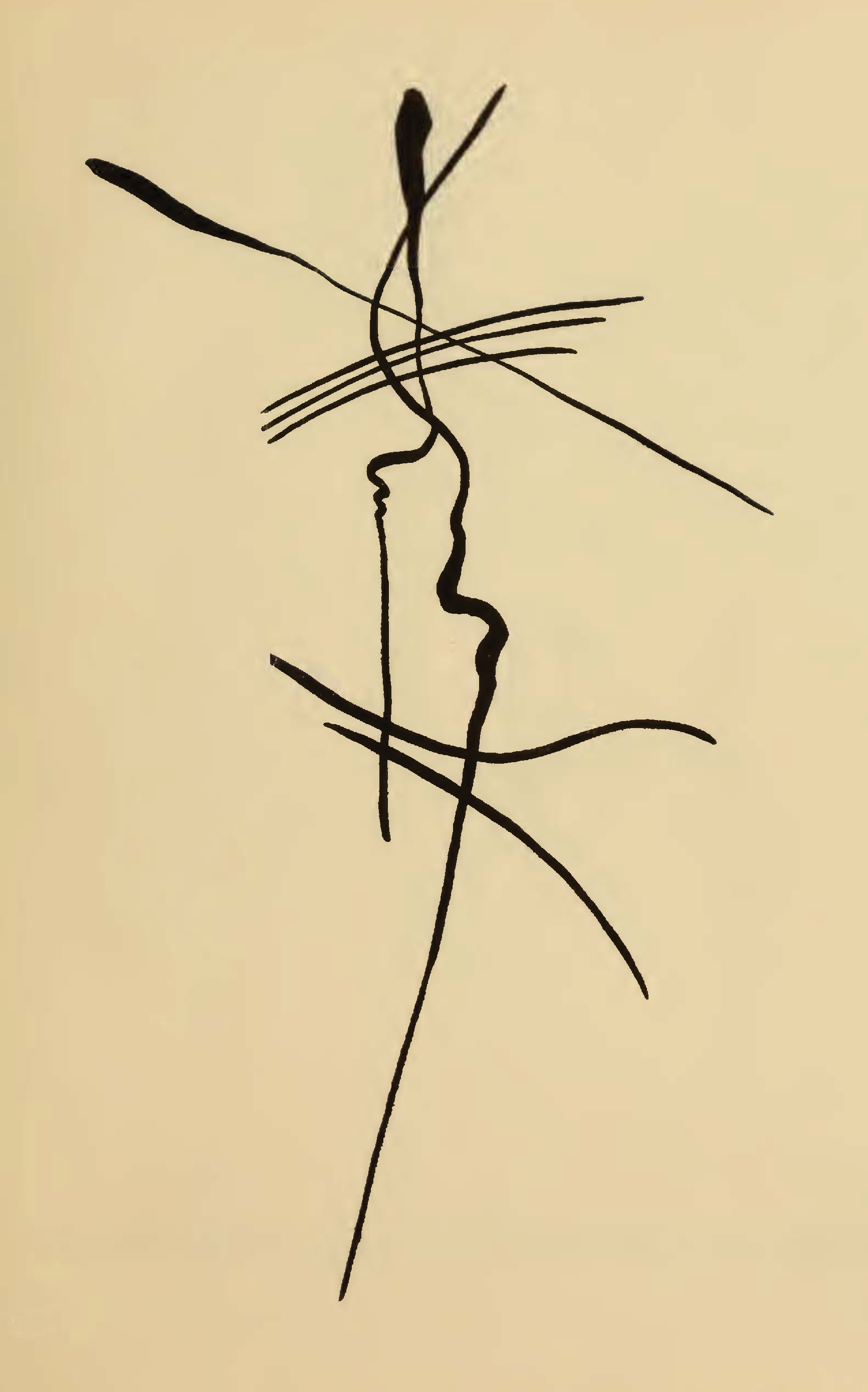

Though painted several years prior to the publication of Punkt und Linie zu Fläche, variations on a number of the examples of “forms” and composition elements or techniques described in that volume may be discerned in Violet Wedge. From the top: Fig. 87, I. Diagonal position "disharmonious." Fig. 88, II. Diagonal position "harmonious." Fig. 62, Contrasting combination of a curved line with an angular line. The characteristics of both acquire a strengthened sound. Left: Diagram 18, Line - Simple and unified complex of several free lines Right: Diagram 19, Line - The same complex complicated by free spirals |

On The Points (1928). Oil on canvas. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-361.php

Kandinsky cautions against trying to force a recognition of the familiar in a painting, while failing to see and experience the painting itself: “The spectator is also too accustomed to look for the ‘meaning,’ in other words an exterior relationship between the parts of the picture. Our era, materialist in life and therefore in art, has produced a spectator who does not know how to simply put himself in front of a painting, and looks for everything possible in the painting but does not allow the picture to work an effect on him” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art, as translated in Kandinsky & Rapelli, p. 67).

Sky Blue (1940). Oil on canvas. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-55.php

Plants swimming by means of their “tails,” an illustration in Punkt und Linie zu Fläche (1926), p. 99, presumably drawn by Kandinsky, based on an article in Die Kultur der Gegenwart (The Culture of the Present), a German encyclopedia published from 1906 to 1926.

Violet Wedge - 1919. Oil on canvas. The Tyumen Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Tyumen, Russia.

https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-630.php

Though painted several years prior to the publication of Punkt und Linie zu Fläche, variations on a number of the examples of “forms” and composition elements or techniques described in that volume may be discerned in Violet Wedge.

From the top:

Fig. 87, I. Diagonal position "disharmonious."

Fig. 88, II. Diagonal position "harmonious."

Fig. 62, Contrasting combination of a curved line with an angular line. The characteristics of both acquire a strengthened sound.

Left: Diagram 18, Line - Simple and unified complex of several free lines

Right: Diagram 19, Line - The same complex complicated by free spirals

Jakov Gotovac, Simfonijsko Kolo, Op. 12 (1926)

Jakov Gotovac (1895–1982) was an ethnic Croatian composer and conductor. He is noted primarily for his opera Ero s onoga svijeta (1935, usually translated as Ero the Joker, literally “Ero from the other world”), which remains the most successful Croatian-language opera in the repertoire. Comprehensive information about Gotovac in thoughtful English translation is elusive, but through the modern miracle of machine translation, his total output appears to comprise 35 opus numbers and 17 early works, including 40 choral compositions, 25 pieces for solo voice and varying accompanying instruments, six miscellaneous instrumental pieces, eight operas and other works for the stage, nine orchestral pieces, and one piece for military band/wind orchestra, titled Our Adriatic (1931). As a conductor and music director, he held a variety of orchestral and operatic posts in then-Yugoslavia from the 1920s through the 1950s, particularly the Croatian National Theatre (a.k.a. the Zagreb Opera) from 1923 to 1958. Later in life, he was a member of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Department of Music and Musicology) from 1977 until his death.

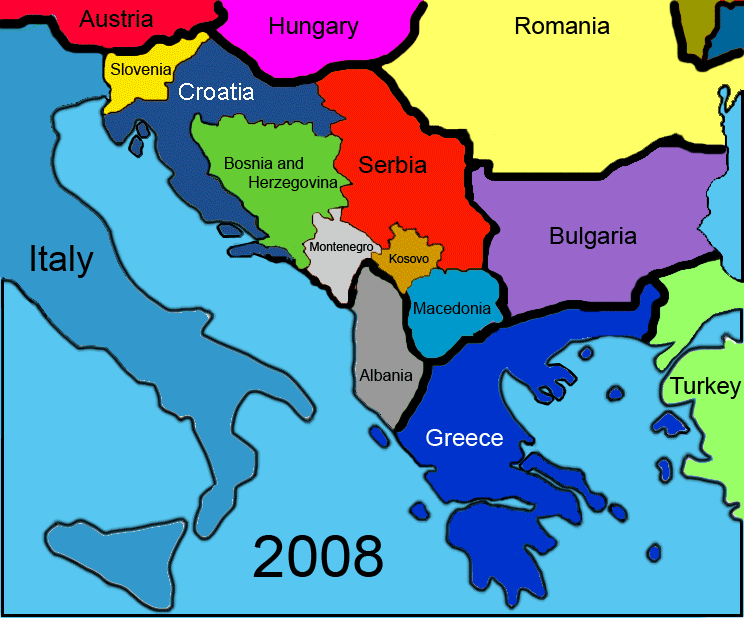

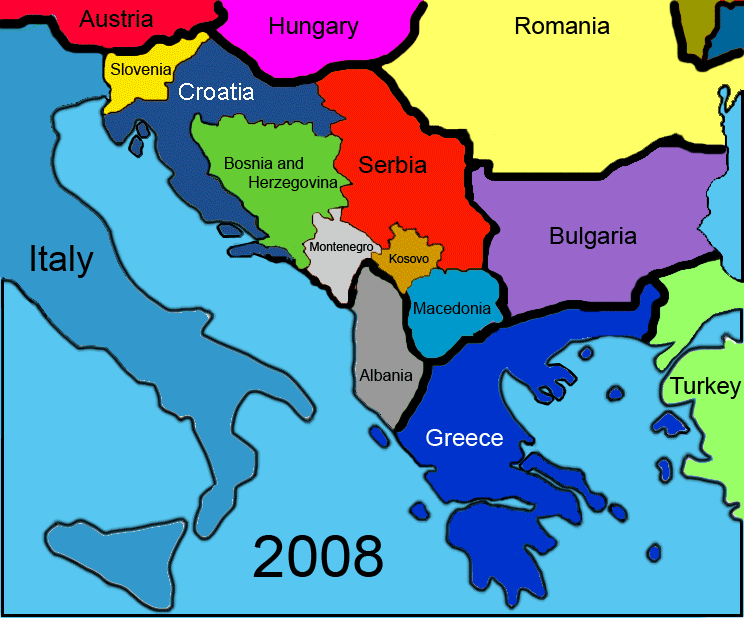

Though a twentieth-century composer, Gotovac stands in common with other late nineteenth-century Eastern European, Romantic Nationalist composers such as Dvořák, Smetana, Glinka, and numerous others, who drew inspiration from their respective national folk histories and musical traditions. The kingdom of Croatia can be dated back to the late 7th Century. Its history involves complex relationships first with the Byzantine Empire, then the Republic of Venice (the northwestern-most tip of modern Croatia is less than 60 miles directly across the Adriatic Sea from Venice), the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. At the end of World War I, Croatia was incorporated into Yugoslavia—a topic unto itself—until 1991 when that political body began to dissolve and the current national landscape of the Balkans emerged: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Macedonia. Gotovac’s home city of Split on the Adriatic coast—the birthplace also of 19th-century composer Franz von Suppé (1819–1895)—was part of Austro-Hungary at the time of his birth; at the time of his death, Yugoslavia; and today, Croatia.

|

|

|

| The Balkan Peninsula in 1881, fourteen years before Gotovac’s birth. The green areas indicate territories held by the Ottoman empire. The region remained mostly unchanged until the First World War. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balkans | The Balkan Peninsula in 1985, three years after Gotovac’s death. The territory of Yugoslavia, created in 1918 from lands of the defeated Austro-Hungarian empire, began to disintegrate when Croatia and Slovenia declared independence in 1991. | The Balkan Peninsula since 2008. Croatia and Slovenia today are member states of the European Union since 2013 and 2004, respectively, and the other Balkan nations are either formal or potential candidates for EU membership at this time. |

The Balkan Peninsula in 1881, fourteen years before Gotovac’s birth. The green areas indicate territories held by the Ottoman empire. The region remained mostly unchanged until the First World War. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balkans

The Balkan Peninsula in 1985, three years after Gotovac’s death. The territory of Yugoslavia, created in 1918 from lands of the defeated Austro-Hungarian empire, began to disintegrate when Croatia and Slovenia declared independence in 1991.

The Balkan Peninsula since 2008. Croatia and Slovenia today are member states of the European Union since 2013 and 2004, respectively, and the other Balkan nations are either formal or potential candidates for EU membership at this time.

The kolo is a folk dance found in several of the Balkan lands, specifically a type of circle dance, i.e., a dance by multiple participants who join together in a circular formation. Circle dances are found in many cultures and are believed to be one of the oldest expressions of social community, with evidence dating from the 12th century. The kolo dance is known also as horo, oro, and kono. The kolo was named to Unesco’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2017. Another, earlier art-music instance of the kolo may be found in Antonin Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance Opus 72, No. 7 (1886).

Gotovac’s Symphonic Kolo, described as “propulsively asymmetric” by Nicolas Slonimsky, was originally written for large symphony orchestra, and premiered in Zagreb in February 1927 (Music since 1900, 5th ed., p. 282). This version for wind band was arranged by fellow Croatian Vilim Marković (1902–1992), a composer, educator, military bandmaster, and performer in the Zagreb Opera orchestra during Gotovac’s tenure there as conductor.

|

Vrlićko Kolo, 1950 pastel drawing by Anka Krizmanić (1896–1987). The town of Vrličko (Vrlika) is about 25 miles north and inland from Gotovac’s coastal home city of Split. Photo by Dmitar Zvonimir, https://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datoteka:1950_Vrli%C4%8Dko_kolo_zgrafito_lesonit_-_215x275_mm.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. |

|

Detail of Vrlićko Kolo. |

|

Player of the mih, a type of traditional Croatian bagpipe. Photo by Joan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piva.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license |

| As a side note, Vrlika is one of several communities noted for a variation of kolo known as the silent, empty, or mute circle dance (Tvrtko Zebec, An Ethnologist in the World of Heritage: Recognizing the Intangible Culture of Croatia, https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_ETHN_132_0267--an-ethnologist-in-the-world-of.htm, accessed 2018-09-11), wherein there is no musical (instrumental) accompaniment or singing; instead only the rhythm of the dancers’ footsteps is heard. This pastel drawing by Krizmanič is shown in conjunction with discussion of this “silent kolo.” But at the upper left, a lone figure is depicted who seems to be holding a large, round object on his knee or lap, or in his arms. While there is insufficient detail for anything more than pure speculation, the general posture and appearance suggests a player of any one of the several varieties of bagpipe instruments found in Croatia. | |

|

An 1892 color print from the Martechelli collection in the Dubrovnik Archive, depicting a circle dance scene from Konavle, at the extreme southernmost tip of Croatia’s Adriatic coast. Note the seated bagpipe player at far right. |

Vrlićko Kolo, 1950 pastel drawing by Anka Krizmanić (1896–1987). The town of Vrličko (Vrlika) is about 25 miles north and inland from Gotovac’s coastal home city of Split. Photo by Dmitar Zvonimir, https://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datoteka:1950_Vrli%C4%8Dko_kolo_zgrafito_lesonit_-_215x275_mm.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Detail of Vrlićko Kolo.

Player of the mih, a type of traditional Croatian bagpipe. Photo by Joan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piva.jpg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

As a side note, Vrlika is one of several communities noted for a variation of kolo known as the silent, empty, or mute circle dance (Tvrtko Zebec, An Ethnologist in the World of Heritage: Recognizing the Intangible Culture of Croatia, https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_ETHN_132_0267--an-ethnologist-in-the-world-of.htm, accessed 2018-09-11), wherein there is no musical (instrumental) accompaniment or singing; instead only the rhythm of the dancers’ footsteps is heard. This pastel drawing by Krizmanič is shown in conjunction with discussion of this “silent kolo.” But at the upper left, a lone figure is depicted who seems to be holding a large, round object on his knee or lap, or in his arms. While there is insufficient detail for anything more than pure speculation, the general posture and appearance suggests a player of any one of the several varieties of bagpipe instruments found in Croatia.

An 1892 color print from the Martechelli collection in the Dubrovnik Archive, depicting a circle dance scene from Konavle, at the extreme southernmost tip of Croatia’s Adriatic coast. Note the seated bagpipe player at far right.

David Maslanka and Matthew Maslanka, Symphony No. 10 “The River of Time” (2018)

The catalog of works for wind ensemble by David Maslanka (1943–2017) incorporates 54 compositions spanning the years 1976 to 2017, and includes 10 concertos for various instruments, seven complete symphonies, and numerous other pieces with a variety of descriptive titles. He also wrote for many other instrument combinations/ensembles and for the voice, but the compositions for wind ensemble represent the largest single medium in his oeuvre. David Maslanka died in August of 2017 after a brief battle with colon cancer.

One of the peculiarities in Western Art Music history is the apparent obstacle that stands between individual composers and the writing of a tenth symphony: Beethoven, Dvořák, Mahler, and Vaughan Williams each produced only nine complete symphonies before their respective deaths; Bruckner never even finished his ninth attempt. Add now to that list David Maslanka, who passed away after completing only one and a half movements of what was to be his tenth symphony for winds. Even more eerie are remarks he made sometime around May 2017: “With each symphony comes an increasing sense of weight, that each has to be ‘important’....[Writing a fifth symphony] has been a marking point of consequence for composers of the past….Symphony No. 9 was worse. This is the serious bugaboo point for people writing symphonies in the western music tradition. ‘No. 9s’ are historically the crowning achievement, and then…death. My No. 9 was written in 2011 and I did not die” (http://davidmaslanka.com/on-composing-and-symphony-no-10, accessed 2018-10-12).

David Maslanka’s son, Matthew (b. 1982), an accomplished musician in his own right and long-time copyist and general musical assistant to his father, completed the composition using what materials had been left behind. He writes, “Dad asked me to finish the work if he were unable to complete it. I drew on my long experience working with dad and his music to first understand the sketches and then to piece them together.” Musical sketches were available to complete the second movement and all of the fourth, but only the very beginning of the third movement and some other fragments offered any evidence to work from there.

David Maslanka had written down his thoughts about the composition of the work as a whole:

I desired to write an important piece. In my vague imagination it was like one of the big symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich, my favorite modern symphonist [Shostakovich escaped the tenth-symphony “curse,” completing a total of fifteen—GSW]. But my inner compass kept dragging me away from that, and pulling back to the humble world of the chorales. A pattern began to emerge of a chorale and a response, the response being the evolution of a radically simple, intimate, and beautiful melody. This process kept repeating itself until half a dozen of these melodic pairings began to emerge—all simple, beautiful, personal, not “important.” At each step I continually questioned whether this was the symphony that needed to be: “Really? Seriously? This is what you want me to do?”—yes. Finding the structural line for the whole piece was extremely difficult. At a certain point, I sensed that a large movement wanted to happen, but it existed only as a hard little node that had begun to rise to consciousness.

Matthew Maslanka describes how he undertook finishing the work:

Dad titled the completed first movement after his wife and my mother: “Alison.” He was writing as my mother was dying of an immune disorder in the spring of 2017. This movement may be seen through that lens, with bitter rage at the coming loss and a beautiful song full of love.

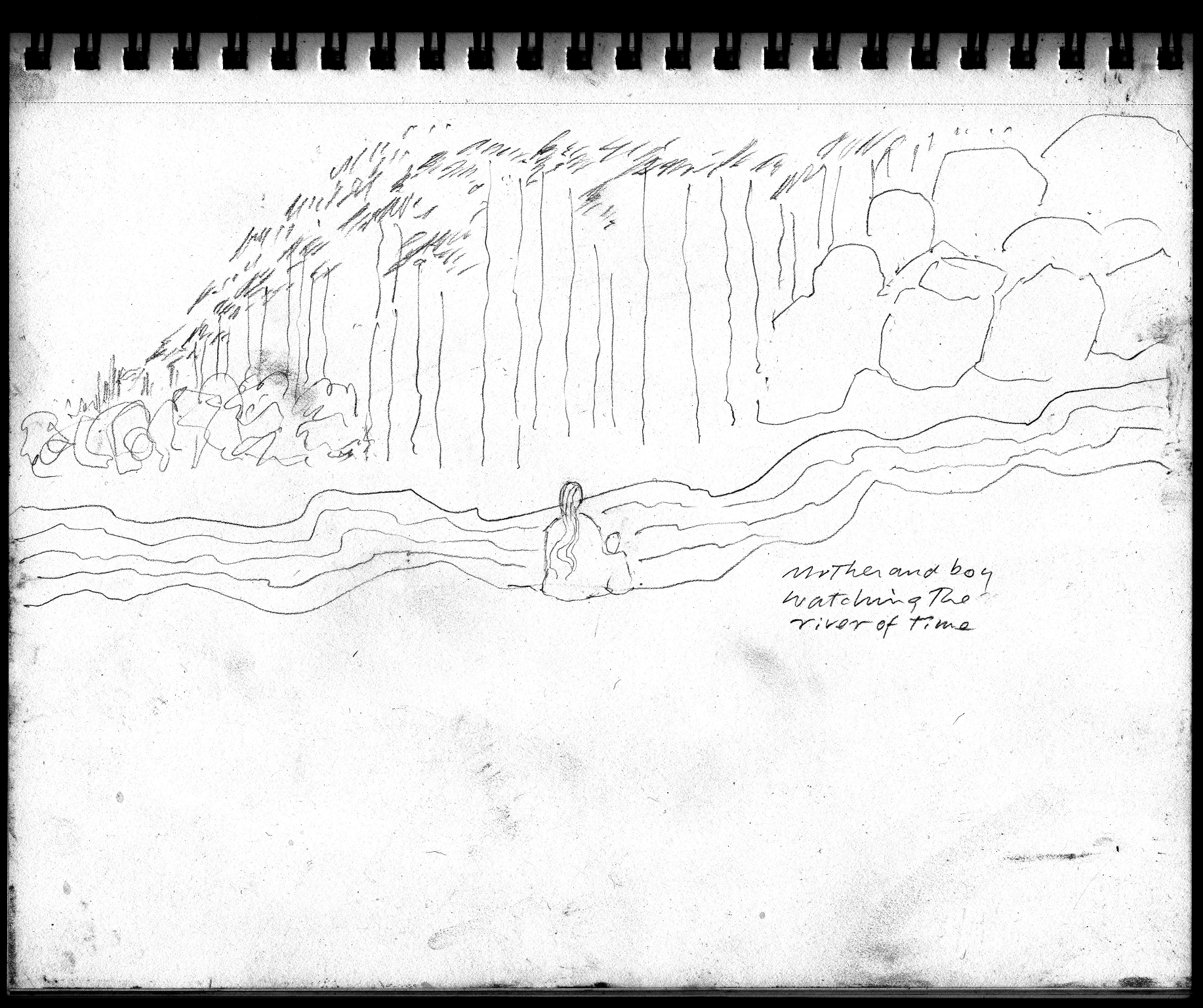

I have named the subsequent movements. The second movement’s title, “Mother and Boy Watching the River of Time,” comes from my father’s final pencil sketch of the same name. It depicts two small figures sitting on a river bank in front of a forest and mountain foothills. The music is largely a transcription of the second movement of the euphonium sonata he wrote for me, Song Lines.

The third movement posed a special challenge. The movement was both at the emotional center of the symphony and the least finished. One tune, marked “The Song at the Heart of it All” in the sketch, became the heart of the work and of the symphony. The full statement of the theme may be found at bar 174, with a quiet restatement in the solo euphonium at bar 217. It is a pure expression of love: my love for my father, his love for me, my mother, sister, and brother, and by extension, love for humanity. The restatement of the opening material, though at first comforting, becomes jarring and unsettled, rising to a dissonant roar. The euphonium soloist is left to scream, “why?!” at world that seems content to keep spinning.

The third movement became my response to the deaths of my mother and father. It is not what dad would have written; rather, it is a synthesis of my mind and his, colored by extraordinary pain and loss. I have named the movement after my father.

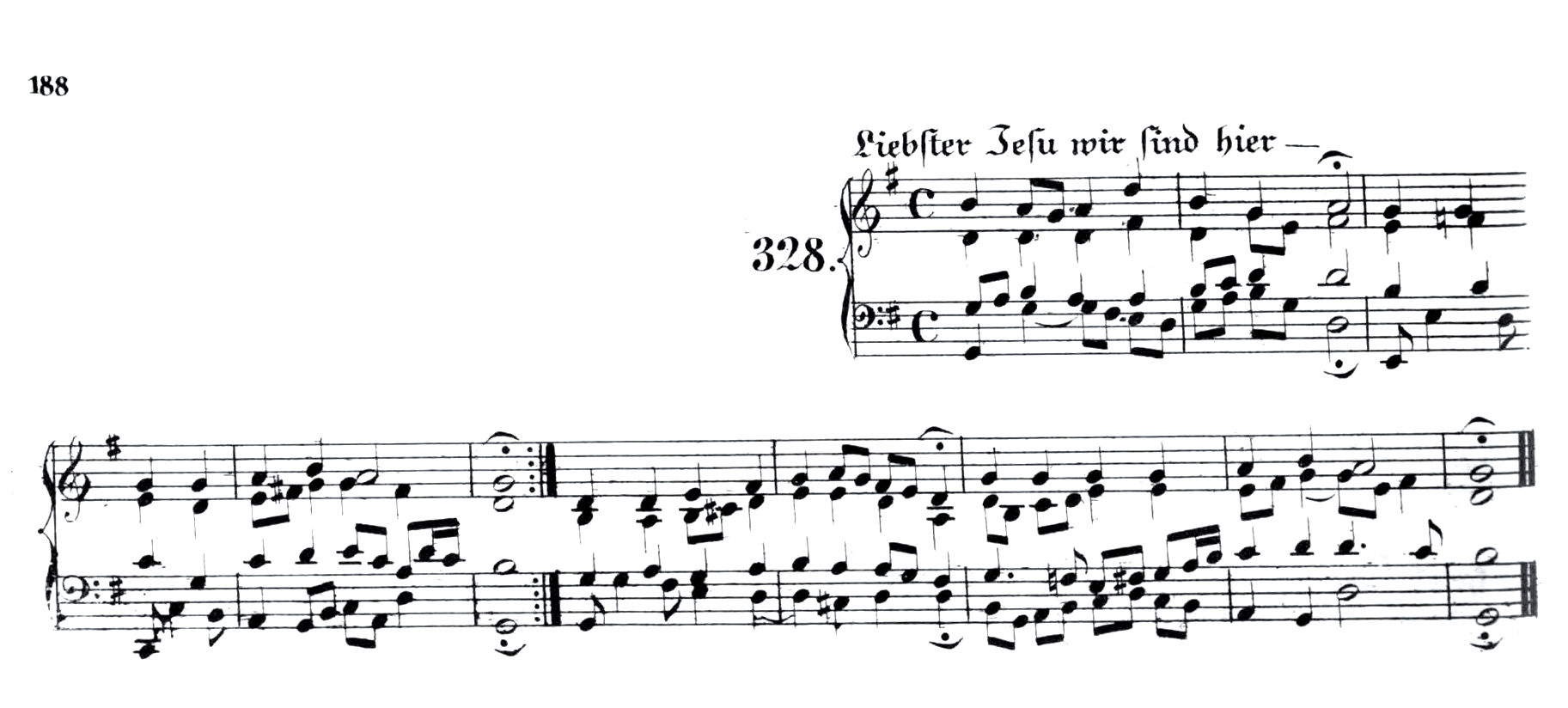

In addition to this “Song at the Heart of it All” melody—recognizable by its vocally-idiomatic use of many repeated notes on the same pitch, a style that makes more sense when there are words to be sung—the other main thematic material of this movement is the chorale Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (“Dearest Jesus, we are here,” tune by Johann R. Ahle (1625-1673).

Chorale #328, “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier,” from 371 Vierstimmige Choralgesänge (371 Chorale Harmonizations), by J.S. Bach (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1784-87). https://imslp.org/wiki/371_Vierstimmige_Choralges%C3%A4nge_%28Bach%2C_Johann_Sebastian%29

This chorale in its entirety introduces the third movement of the symphony, and the second phrase of the melody is the source material for one of the primary themes of the rest of the movement.

Matthew continues in describing the final movement:

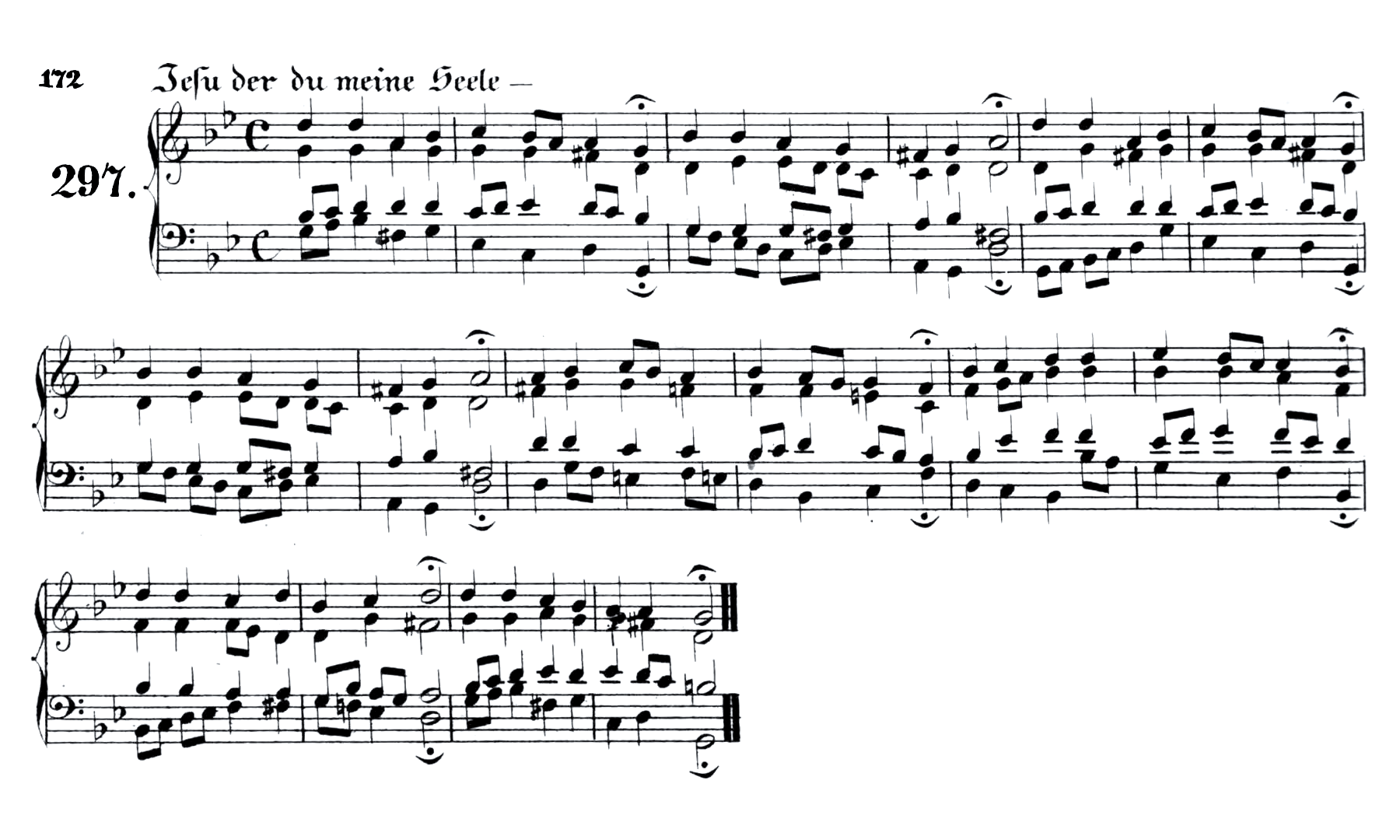

The fourth movement, “One Breath in Peace,” is the acceptance and ability to move forward after loss. The long solo lines for oboe reflect and extend the bookending chorale, Jesu, der du meine Seele [“Jesus, You, who are my soul,” tune and original text by Johann van Rist (1607–1667)—GSW]. Dad’s customary morning practice was to play one chorale from the Bach 371 Chorales. He would sing each line as he played along on the piano. In this way, he came to deeply understand these miniature jewels of western music. I have closed the symphony with the last statement of the chorale, with the pianist singing the tenor line. I hope you will hear his voice in it.

Chorale #297, “Jesu der du meine Seele,” from 371 Vierstimmige Choralgesänge. The final two bars of the tenor part close out the final movement of the symphony.

Read more about the symphony in the expanded critique "David Maslanka and Matthew Maslanka, Symphony No. 10 'The River of Time'" by GSW member Jeffrey A. Ohlmann.