Saturday, December 15, 2018 – 3 p.m.

The Steeple Center

14375 South Robert Trail

Rosemount, MN 55068

Sousa: The Gladiator March

Arrieu: Dixtuor pour Instruments à vent – with guest artist Neoteric Chamber Winds

Van: Concerto for Guitar and Wind Ensemble – with guest artist Christopher Kachian

Markowski: Machiavelli’s Conscience – with guest artist Neoteric Chamber Winds

Villani-Côrtes: Sinfonia No. 1

Grand Symphonic Winds is joined by special guest artists Chris Kachian, guitar, and Neoteric Chamber Winds – “the Twin Cities’ modern mix of woodwinds and brass” – for a program showcasing a new concerto for guitar and wind ensemble by Jeffrey Van, unusual 20th- and 21st-century compositions for smaller groupings of winds and brass, and the Sinfonia No. 1 from 1998 by the dean of Brazilian composers, Edmundo Villani-Côrtes.

Unless otherwise noted, our concerts are free and open to the public. Help support our mission to bring great music to the Twin Cities – share this information with your friends. Sign up for our mailing list and receive reminders for our events.

Program Notes

John Philip Sousa, The Gladiator (1886)

John Philip Sousa (1854–1932) was born in Washington, D.C. His parents were immigrants: his father, João António de Sousa, was born in Spain of Portuguese parents, and his mother, Maria Elisabeth Sousa (née Trinkhaus), was born in Bavaria; they met in New York where Antonio was a musician in the United States Navy. The younger Sousa started attending Marine Band rehearsals with his father at the age of 11, and in 1868 he enlisted as an apprentice musician. He continued his study of music, and became a very good violinist. Sousa became the fourteenth conductor of the United States Marine Band in 1880, and held that position for twelve years. Sousa left this position in 1892 to form his own professional band, the Sousa Band. This ensemble performed from coast to coast on numerous tours in the United States, and established an international reputation throughout Europe on four very successful tours. (Biographical information adapted from John Philip Sousa: People Who Live in Glass Houses (musical score), Kansas City: Wingert-Jones Publications, 2004.)

By 1886 Sousa had written at least 25 marches (among which are both President Garfield’s Inauguration March (1881) and In Memoriam: President Garfield’s Funeral March (1881)), four operettas, and numerous songs and miscellaneous instrumental pieces, but it was only with The Gladiator that he achieved a major success. Sousa and his music since have become institutionalized in modern musical America, and it is easy to forget that once it was new and previously unheard. To help cast the right light, the following is a selection of other notable events of the year 1886:

- The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson is published (5 January)

- The first train shipment of oranges departs from Los Angeles, via the transcontinental railroad (14 February)

- An attempt to expel Chinese immigrants from Seattle, WA, leads to violence and the death of two people (8 March)

- A peaceful labor protest in Chicago devolves into The Haymarket Riot when a dynamite bomb kills seven police officers and four civilians (4 May)

- The United States Supreme Court rules in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad that the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution applies to corporations in the same way it applies to individuals (17 May)

- The Atlanta Journal runs the first advertisement for Coca-Cola (29 May)

- Forty-nine-year-old U.S. President Grover Cleveland, serving the first of his two non-consecutive terms, marries 21-year-old Frances Folsom at the White House (2 June)

- Arturo Toscanini, aged 19, on tour with an Italian opera company in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, conducts Verdi’s Aida from memory after the singers refused to perform for the locally-hired conductor (25 June)

- After thirty years of fighting, Apache leader Geronimo surrenders to the U.S. Army in Arizona (4 September)

- Begun in France in 1876 and transported to the U.S. in 1885, the completed Statue of Liberty is officially dedicated in New York Harbor (28 October)

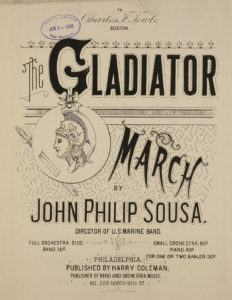

The Gladiator is one of about 50 marches by Sousa with a title started by the definite article The. The rest of the title typically refers to an (anonymous individual or position, e.g., The Crusader (1888), The Bride Elect (1897), or The Diplomat (1904), or to a group, e.g., The Loyal Legion (1890), The Naval Reserve (1917), or The Legionnaires (1930). The first printing of The Gladiator sheet music bore a dedication to one Charles F. Towle, a journalist of minor note for the Boston Evening Traveller, but precisely why is unknown (Paul E. Bierley, The Works of John Philip Sousa (Westerville, Ohio: Integrity Press, 1984), 56, as cited in https://www.marineband.marines.mil/Audio-Resources/The-Complete-Marches- of-John-Philip-Sousa/The-Gladiator-March/, accessed 2018-10-29).

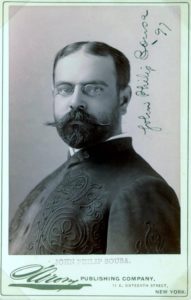

Left: Photo of Sousa ca. 1897. Right: 1888 edition of The Gladiator bearing the dedication to Charles F. Towle. Note this particular publication is an arrangement of the march for one or two banjos.

Claude Arrieu, Dixtuor pour instruments à vent (1967)

Louise Marie Simon (1903–1990) attended the Paris Conservatoire hoping to become a piano virtuoso, but she turned to composition and was a student of Paul Dukas. For reasons that are not fully clear, in 1926 she adopted the pseudonym Claude Arrieu, the name under which she worked and published for her entire life. It has been postulated that she took this name for personal, familial reasons; but also speculated that there were professional reasons. Arrieu was by no means unique as a woman studying at the conservatory, and by all accounts she was well-accepted and well-regarded by her peers, both male and female. But the French music-publishing industry remained a more conservative body, and Arrieu may have perceived that a gender-ambiguous name might work more in her favor. She graduated with a premier prix (an honorary designation denoting a very high level of proficiency) diploma in 1932, and while she had a successful working career as a composer, she did not achieve the world-wide fame of her conservatory contemporaries such as Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) or Marcel Duraflé (1902–1986). Nevertheless, her compositions were performed by the leading musicians of the day, offering an indication of her position in French musical society. (Laura Ann Hamer, Musiciennes: Women Musicians in France during the Interwar Years 1919-1939, Doctoral Dissertation, Cardiff University, 2009).

Louise Marie Simon (1903–1990) attended the Paris Conservatoire hoping to become a piano virtuoso, but she turned to composition and was a student of Paul Dukas. For reasons that are not fully clear, in 1926 she adopted the pseudonym Claude Arrieu, the name under which she worked and published for her entire life. It has been postulated that she took this name for personal, familial reasons; but also speculated that there were professional reasons. Arrieu was by no means unique as a woman studying at the conservatory, and by all accounts she was well-accepted and well-regarded by her peers, both male and female. But the French music-publishing industry remained a more conservative body, and Arrieu may have perceived that a gender-ambiguous name might work more in her favor. She graduated with a premier prix (an honorary designation denoting a very high level of proficiency) diploma in 1932, and while she had a successful working career as a composer, she did not achieve the world-wide fame of her conservatory contemporaries such as Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) or Marcel Duraflé (1902–1986). Nevertheless, her compositions were performed by the leading musicians of the day, offering an indication of her position in French musical society. (Laura Ann Hamer, Musiciennes: Women Musicians in France during the Interwar Years 1919-1939, Doctoral Dissertation, Cardiff University, 2009).

Authors Karen Pendle and Robert Zierolf, writing in Women & Music: A History (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001), describe Arrieu/Simon’s style and experience as

…personal neo-classicism. She learned much from the French neoclassic tradition prevalent during her formative years, but her music is not so much a reminiscence of Ravel or Poulenc as it is a corollary to their styles.

In 1946 she began a long relationship with French radio and television studios, and she was one of the first composers to work with Pierre Schaeffer [1910–1995] at Radiodiffusion Française [the public-service broadcasting network from 1944 to 1949]. Schaeffer is usually credited with inventing musique concrète, an early phase of electronic music in which acoustic sounds are manipulated electronically. Arrieu quickly lost interest in this experimental music….Nevertheless, the studio experience was ultimately valuable as an apprenticeship for composing scores in other media. At least thirty film scores and more than forty radio scores attest to Arrieu’s interest in and facility with the media.

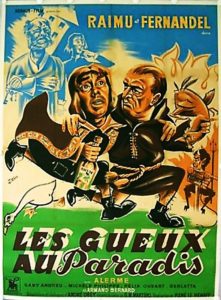

Posters from two films with music by Claude Arrieu. Left: Hoboes in Paradise (1946). Right: Le Tombeur!!! (1958)., translated variously as The Heartthrob or Casanova.

Dixtuor (“Dectet,” or piece for 10 wind instruments) is scored for the unusual combination of 2 flutes (one doubling on piccolo), oboe, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, horn, trumpet, and trombone. The work is in five movements, but if the fourth is construed as either a bridge between the third and fifth, or simply as an extended introduction to the finale, the general shape of the composition follows a traditional four-movement plan. Arrieu muddles things somewhat by not really settling on one mood for each of the two interior movements; both have a mixture of moderate and more dance-like sections. The overall mood of the piece progresses from a general insouciance in the first movement, to a more shifting uncertainty in the interior movements, then finally a burst of certainty in the finale–until the very final bars introduce, if not a new question, at least a reminder that doubt exists.

Jeffrey Van, Concerto for Guitar, Op. 73b (2018)

Guitarist and composer Jeffrey Van (b.1941) has performed in Carnegie Hall, London’s Wigmore Hall, and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. He is a founding member of The Hill House Chamber Players, with whom he performed for thirty years. Van has taught master classes throughout the United States, and earned an M.F.A. from the University of Minnesota School of Music, where he was a Lecturer in Guitar for several decades. Former students include Sharon Isbin, John Holmquist, Christopher Kachian, and many past and current members of the Minneapolis Guitar Quartet.

Van’s list of works comprises 73 original opus numbers and another 14 arrangements, the bulk of which, unsurprisingly, either are for or include one or more guitars. But of the total, fully half include chorus or solo voices. Van describes his early musical experience:

I began studying classical guitar a few months short of my eighth birthday, and sang in many choirs from an early age. Since there was no guitar major available for my undergraduate music degree from Macalester College, I was a vocal major. During grad school at the University of Minnesota I auditioned on guitar, and convinced the school to appoint my esteemed guitar teacher, Albert Bellson, to the adjunct faculty, so I created the guitar major program there. I know the guitar and the choir intimately, and how to combine them successfully, so it is natural that I keep getting asked to write for them.

Concerning his compositional progression to the larger instrumental forces of a concerto—which, on paper, seems to preceded only by his Reflexiones Concertante: Concerto for Two Guitars and Chamber Orchestra (2002) and a smattering of other chamber works involving various combinations of strings and winds—Van says, “I was fortunate to be asked to play a lot of chamber music with guitar, beginning in my teens. I have performed with a boatload of orchestral musicians, and have many friends in the Minnesota Orchestra. So, I soaked up a lot of information and a sense of the characteristics of the standard orchestral instruments. I played quite a few concertos, so I got a first-hand sense of what works and what doesn’t.” He also states from a very practical point of view:

The works you “think about” writing seldom get written, because it is open-ended; the ones which do get completed are the ones which people ask you to write by a certain deadline for a specific performance….I always thought I had a guitar concerto in me, but nobody ever asked me to write one, until my friend and colleague from Wake Forest University commissioned [Reflexiones Concertante] for the two of us to play and record. The second [large instrumental] work was the large war piece, Reaping the Whirlwind (2014) [twelve movements for SATB Chorus, mezzo soprano and baritone soloists and chamber orchestra], a piece I wanted to do for many years, but it didn’t happen until someone demanded it. Likewise, the third work, Op 73, the concerto for one guitar and wind ensemble (and orchestra version), commissioned for and by my former student and great friend, Christopher Kachian at the University of St. Thomas.

While the guitar is not altogether uncommon as a solo instrument with the symphony or string orchestra, the instrument is not a frequent visitor to the wind ensemble stage. But there are precedents: Samuel Adler (b. 1928), Concerto for Guitar and Wind Ensemble (1996), Loris Chobanian (b. 1933) Armenian Rhapsody for Guitar and Symphonic Wind Ensemble (2007)—also premieried by Christopher Kachian and Matthew George—Ken Johnson, Chamber Concerto for Guitars and Winds (2010?), and Stephen Goss (b. 1964), A Concerto of Colours (2017) are some readily accessible examples. About Jeffrey Van’s concerto, soloist Christopher Kachian says, “I am always so very excited to premiere a new work for guitar….[this concerto is] part of a long-term project that Matt George and I have conceived to add to the repertoire for guitar and wind ensemble—a very small yet deserving repertoire indeed.”

The solo part is performed on a nylon-strung classical guitar with amplification. Composer Van writes that amplification is merely a tool “to level the playing field somewhat” between the soloist and the ensemble, while still allowing the soloist “to play with some dynamic variation and expression. The goal being to do this while maintaining the natural sound of the guitar, and the perfect result is when the audience hears the guitar well, but is not even aware that it is being amplified.” Christopher Katchian remarks, “I first started using amplification once it became the norm in the flamenco world. I then started using it in chamber music with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and Minnesota Orchestra…they didn’t even notice anything other than that I was louder. Success! In the wind ensemble context it is essential, needless to say. The guitar and winds repertoire is a new world.” Jeffrey Van continues the thought:

It was a challenging and interesting process using the wind ensemble for the accompaniment in a concerto for guitar, since the wind ensemble can be a formidable force, and despite modern technology, no matter how much you amplify a classical guitar, it’s never going to be a nine-foot Steinway. I debated about numbers and size, but in the end, I just decided to assemble a palette of instruments which I felt would lend itself to this purpose. While the ensemble is in a supportive role, I always strive to give all the instruments material that is interesting and rewarding to play, and to give the full ensemble “its moments” to shine. And, since by definition, a concerto is to feature the solo instrument, the guitar’s first entry is a substantial unaccompanied statement, and the soloist enjoys a long “soliloquy-cadenza” in the second movement, and quiet sections of interplay with the orchestra bells. There are many concertos for guitar and orchestra, but few for guitar and wind ensemble. I believe the format will continue to expand, and become a fertile field of exploration for many composers.

Michael Markowski, Machiavelli’s Conscience (2017)

Michael Markowski (b. 1986) graduated from Arizona State University with a B.A. in film practices, but studied music composition privately. His list of compositions includes 81 items, and ranges through theatrical music, film scores, chamber music, short orchestral pieces, and music for wind band at various levels of difficulty.

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469–1527) is a member of that rarified group of persons whose name has achieved the status of an adjective. His notoriety primarily is owed to his volume The Prince (1513), in which he describes, and appears to endorse, a variety of often unscrupulous behaviors that state leaders may and must engage in to maintain their power and status. A modern person—be they politician, CEO, or in any position of power—who seems to engage in self-serving schemes without regard for usual ethics and morals is thus said to be “Machiavellian.”

Concerning this composition, Markowski writes, “…[Machiavelli] wrote comedies and plays and songs, too….I became fascinated by how a person like this could possibly come to some of these morally-outrageous but politically-justified conclusions. At its core, I think the octet imagines the cogs of such a conflicted mind at work as it searches for a way to justify these radical ideas in the name of power and ego.”

Edmundo Villani-Côrtes, Sinfonia No. 1 (1998)

Edmundo Villani-Côrtes (b. 1930) is highly regarded as one of the premiere living Brazilian composers. The child of musical parents, he first learned to play the cavaquinho [a type of small, 4-string guitar originally from Portugal] through observation of his brother’s playing of the instrument. He also cites the music he heard on the radio as a youth as an early musical influence, from the Glenn Miller Orchestra during World War II to the music used in radionovelas that his mother listened to: “I recognized a certain work because it was musical background of novels. I ended up having contact with the classics through the novels. Ravel, Stravinsky, as background.” At seventeen he started his formal music studies, including piano performance at the Conservatôrio Brasileiro de Mûsica in Rio de Janeiro, and completed them in 1954. During the time of his studies there, he also performed as a pianist in nightclubs, as well as participating in the Radio Tupi Orchestra in Rio de Janeiro, under the leadership of maestro and arranger Orlando Costa (1919-1992). Villani-Côrtes remarks that at that time, because recorded or electronically-produced music was uncommon, “if there was no musician, there was no music.” He later earned his Master of Music at the Rio de Janeiro’s Federal University, and a Doctor of Music at the Musical Institute of Arts, Sâo Paulo State University.

His professional career has been active and diverse. As a pianist and arranger, he has produced more than 1000 musical works for television and recordings from the 1970s to the 1990s. In art music, he has composed over 200 works for solo instruments, duets, trios, quartets, wind ensembles, and symphonic orchestra, and has been a winner of numerous awards for composition.

Speaking of his own musical style and influences, he says “I look for in the instrument what I want to find.” Although he was a student of Camargo Guarnieri (1907–1993) and many relate his own music to the Nationalist current, Villani-Côrtes disagrees and says that his composition is the result of a need for expression: “I’ve never studied folklore. I never researched anything and I do not consider myself a nationalist. If eventually the resources I use coincide with this [nationalist] school, it is something purely casual.” He does not feel bound by any specific compositional approach:

If at a certain moment of the song I have to put a rhythm of xaxado [a particular dance of Brazil], I place it. If in a certain place I want to do a cluster effect or an atonal chord, I’ll do it. I use everything because I think if you stick to a school, you’re the school, not yourself. I’m the school. School is what I think I should do and school is what I know because I use the resources I have.

To make composition often is independent of the fact of having knowledge, having good technique, etc. You can analyze compositions, know music, have knowledge of counterpoint, harmony, anyway, but if you are not in order to make music, if you are without will or enthusiasm, nothing comes out.

Villani-Côrtes’ musical style mixes elements of classical music with urban popular music, and he makes a point of calling his art “simple and unpretentious.” Curiously, perhaps it was precisely this unpretentiousness that, in the end, makes of Villani-Côrtes one of the most alive Brazilian composers of the present time. “I never intended to be a famous composer, a school, a music genius. My business was always to write what I liked, which I found interesting. I like it, it’s here and that’s it.”

(Biography and other remarks adapted from http://www.brazilianmusicpublications.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=46:edmundo-villani-cortes&catid=28&Itemid=118, accessed 2018-11-02, and https://www.villanicortes.com.br/ via Google Translate, accessed 2018-11-02.)

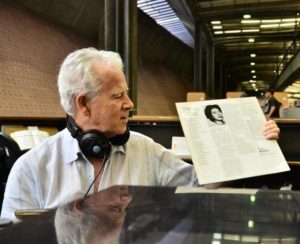

Edmundo Villani-Cortes ca. 2015. Photo by João Mussolin, https://www.ufjf.br/secom/2015/10/28/circuito-musica-brasilis-homenageia-mario-de-andrade-e-villani-cortes-no-cine-theatro-central/

Symphony No. 1 is considered today one of the classic symphonic pieces of the Brazilian original repertoire for bands. It was commissioned in 1997 by the Conservatory of Tatuí for the Symphonic Band, the Brazilian Wind Orchestra at that time. Completed in 1998, it was premiered simultaneously in May of that year, at the Procópio Ferreira Theater of Tatuí, and at the Winter Festival of Campos do Jordão, which also was broadcast to the entire state of São Paulo by Cultura Radio station.

The symphony is in three movements:

- Moderato

- Adagio

- Allegro moderato

All three are fluid in tempo, with many changes both gradual and abrupt. The first and the third movements are structured in modified sonata form—the leading traditional form for major musical works since the time of Haydn and Mozart—but the thematic development is an exemplar of Villani-Côrtes’ creative musical thinking. The second movement is in the form of a song. The influences of, and Villani-Côrtes’ love for, Brazilian music, Bach, Debussy, and Ravel can clearly be heard. In the orchestration, Villani-Côrtes goes beyond the typical classical habits mainly through the use of mallet percussion (marimba, xylophone, vibraphone, and glockenspiel) along with piano, and also the woodwinds in extreme registers. (Adapted from Dario Sotelo, liner notes to Banda Sinfônica do Conservatório de Tatuí – 20 anos, Conservatório de Tatuí, CD, 2012.)

Program notes © 2018 by Jeffrey A. Ohlmann for Grand Symphonic Winds, except where noted. The author wishes to thank Jeffrey Van and Christopher Kachian for their personal correspondence and contributions toward the notes on the concerto.